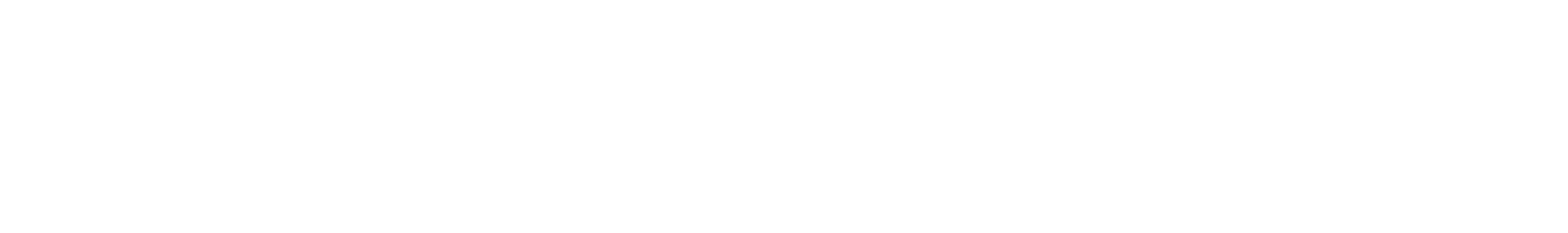

It was a warm, spring day on April 24, 1980, when three-year-old Jeffrey Dupres went to the next-door neighbours’ house to play with his best friend, Rodney.

Jeffrey’s mother, Denise McKee, was doing laundry in their Slave Lake, Alta. bungalow at the time, and thought nothing of it; She and her husband Ray Dupres had only moved to the area three months earlier, and she was delighted that Jeffrey and Rodney, who was a couple years older than her son, got along so well. The pair were forever traipsing back and forth to one another’s houses.

McKee’s sense of ease was short-lived. Just twenty-five minutes after Jeffrey left for Rodney’s house, Rodney rang her doorbell, wondering where his friend was.

Jeffrey had disappeared.

More than 42 years later, McKee still has no idea what happened to her son. There’s not a day that’s since passed — and there have been more than 15,000 of them — when she hasn’t thought of him and wondered. In her best-case scenario, Jeffrey was kidnapped and is alive today, perhaps unaware of the events that took place so long ago. At worst, well, she tries not to think about that. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, she holds out hope.

As I’ve said to the media many times, I understand the absurdity of a grey-haired woman still looking for her toddler. But as a mother, losing a child never goes away. You never stop wondering.

Denise McKee

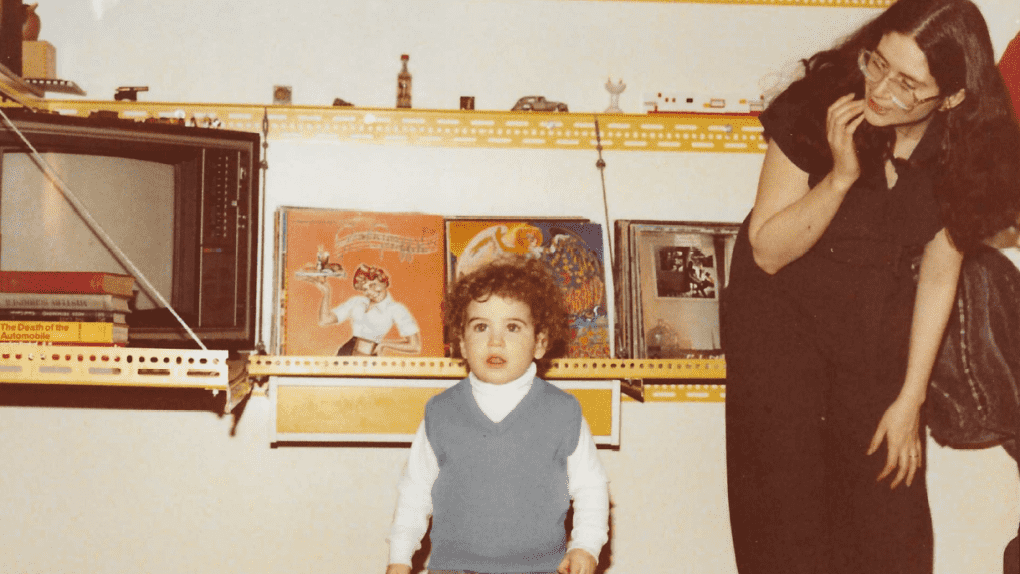

Eleven years ago, McKee, an Ottawa resident since 1993 (and earlier — Jeffrey was born at the Grace hospital here, in 1977), created a Facebook page, “What Happened to Jeffrey Dupres?” with the hope of crowdsourcing a solution to the mystery. Last month, she started a GoFundMe campaign to raise funds so a Private Investigator could set up a tip line (recoveragency.com), as well as examine possible theories and old leads, re-interview people who knew Jeffrey, raise awareness about the case, and employ means unavailable or not used in the early 1980s, including commercial DNA analysis and genealogy websites. Anything to uncover Jeffrey’s fate and his possible whereabouts today.

As part of this new investigation, she commissioned UK-based forensic artist Tim Widden to create an age progression portrait of what Jeffrey might look like today, at age 45. There’s also a $5,000 reward for information on Jeffrey’s whereabouts.

She acknowledges that it’s all a long shot. “It’s more likely that Jeffrey would find me than me finding him,” she admits.

But what else is a mother to do?

The immediate response to Jeffrey’s disappearance, according to McKee, was uneven. The police did little, she says, perhaps partly owing to their focus on the bushfires that surrounded Slave Lake at the time. But she often wonders, perhaps, if it was because of the area of town she lived in, where many Indigenous residents also lived, that a missing youngster might not have been a priority for the authorities.

When McKee suggested that the roadblocks that were already in place because of the fires also be used to look for Jeffrey, she was told that was impossible if there was no information available about the specific vehicle they might be looking for. Police did, however, come and search her house, twice, and administer a polygraph test. It took more than 20 years, she says, until she was told she was no longer a suspect.

By contrast, the response from residents was resoundingly positive, if ultimately fruitless. After McKee asked Slave Lake’s disaster committee to take the lead, hundreds of residents locked arms, literally, to form a search party that stretched from one end of town to the other.

“I was marching in the search,” McKee recalls, “and the man beside me, who didn’t know who I was, worked at one of the plants threatened by the fires. He called his boss and told him he had to go on the search. His boss said no, so the man quit. He got his job back right away, but that’s how important the search was to people. The town embraced me.”

Then when someone mentioned the possibility that Jeffrey had wandered into a nearby creek, neighbours — these were largely oil-industry people — bulldozed it so they could search the bed.

“There were grown men with rakes,” McKee says, “crying because they weren’t looking there to find him alive.”

When it became clear that Jeffrey wasn’t in the town, at least not in the open, the RCMP was asked to call in the Armed Forces to search the woods. They balked at the request, saying that the province had to initiate such a search. So McKee reached out to Alberta MLA Larry Shaben, MP Jack Shields and premier Peter Lougheed, after which approximately 100 soldiers joined the search, with RCMP aiding from a helicopter with an infrared camera. There was no sign of Jeffrey, however, and after four days scouring the bush — nine days since Jeffrey went missing — the search was called off.

Meanwhile, other leads materialized. One woman and her granddaughter said they saw a young couple — a woman in her 20s and a man in his 30s — stop their vehicle and pick up Jeffrey on the day he disappeared, about a mile from his home. Under hypnosis, further details from the incident emerged: it was a late-model Chevy truck with a unique blue paint job, and Northwest Territories licence plates. A description of the couple was also determined.

McKee doesn’t doubt most of that story, but she has a hard time convincing herself it was Jeffrey. “It was a warm day and there were groups of children playing along the street. He would have stopped and played with somebody. I checked with the kids who were playing. They didn’t see him.

“But I’m not willing to disbelieve,” she adds. “Part of me wanted to believe it, that this nice young couple took him. But you have to discount what you want to believe.”

Life, after a fashion, continued. “But you don’t know how empty your life is,” McKee recalls. “Just empty. That was my job; looking after him. And after that, every time I went out, I looked for him, on the street, at the mall, everywhere.”

Eventually, however, what she was looking for ceased to exist. The three-year-old would, hopefully, become a 10-year-old, and then 20. But would a parent recognize a 20-year-old son she hadn’t seen since he was three?

At the same time, on top of the anxiety and worry that she experienced, there was the self-reproach she felt. That presses on her to this day.

“I feel very guilty for losing Jeffrey,” she says. “I tell people that I have to be the world’s most helpful, tolerant person, and that’s not hard because I can’t quite be judgemental, can I? I once sent my child out to play and he never came back.”

McKee and Ray had two more sons together — Christopher in 1983 and Mark in four years later. McKee remembers Chris being taunted as a youngster, with schoolmates saying that his mother killed his brother. “I understand that they wanted to believe that,” she says, ”because it would have been so much nicer for Slave Lake than this mystery.”

She and Ray separated in 1993, after which she and the boys moved to Ottawa to be closer to her family. But that, too, was difficult, knowing that she was nearly 3,000 kilometres away from where she last saw Jeffrey.

Meanwhile, people have come forward over the years with information that, so far, hasn’t panned out. A schoolteacher in Saskatchewan said she taught Jeffrey in her Grade 4 class. A woman in Cornwall told police that her husband killed Jeffrey. Some have claimed to be Jeffrey, including one man from the southern U.S., and another who sent McKee a photo of him in front of what could be the truck that the witness believes she saw Jeffrey get into that day. In cases where someone claims to be her son, McKee asks them to take a DNA test or go to the police. That often ends the conversation.

“It changed me,” she says of the ordeal. “That’s what I am. I want him to be alive, so badly. Although knowing what his life might have been like, I don’t know. It’s all so painful.

“But there has to be some definitiveness, or it’s not over,” she adds. “As long as I don’t have closure, I still have hope, right? That’s how I think about it; I trade one off for the other. Maybe it’s not a lot of hope, and maybe I don’t really believe it. But I want to. I cling to it.”

Anna J.

Originally from Sydney, Australia, I'm the Founder of Recover, a Private Investigation & PR agency headquartered in Vancouver.

I earned my Bachelor of Journalism minoring in film and Criminology, and was Candidate for the MFA Creative Writing Program at the University of Victoria.

I began my professional career in publishing at Wiley, and my journalism career reporting on baseball from Brisbane to Boston.

I spent over 10 years reporting, and my last beat was crime, which led my move into to Private Investigation.

As Licensed Private Investigator, I work on complex cases including homicides, large-scale civil suits, and missing persons.

I work with PI firms across BC & the US, and appear in the media for my work.

I run on prayer and coffee.